On November 1, 1920 Kevin Barry was executed. This is a little-known story from his grand-niece Síofra O’Donovan

Síofra O’Donovan grew up in the shadow of her ‘boy-hero-great-uncle’. Here she tells how the teenage rebel lived life to the full as a UCD student — and how she found it hard to escape his ghostly presence.

When it came to my great-uncle Kevin Barry enrolling at University College Dublin on October 13, 1919 to study medicine, the college was bursting at the seams.

As one observer put it, “Those who had been too young to offer themselves as cannon fodder [in the Great War] were clamouring for higher education.” The enrolment for first year Medicine was 193, 32 of them women.

It was during this time that Kevin’s dancing took off in the dance halls of Dublin. Dancing, drinking, betting and flirting were some of Kevin’s favourite pastimes in his short university career.

A fellow UCD student, Honoria Aughney, met Kevin at a céilí. They were dancing to The Siege of Ennis, a dance in which you change partners, and Kevin said: “I didn’t know the Carlow girls knew anything about dancing”, to which Honoria answered: “And I didn’t know the rugby players knew anything about it either.”

Kevin also loved betting. I once found his racing card from the Metropolitan Baldoyle Races for Saturday, May 10, 1919, full of scribbles on the back about major sea routes — distances by sea between America, England, New Zealand and Hong Kong.

I wonder if this was preparation for a geography exam.

The Matassa Coffee House had a large IRA clientele, including Kevin and his friends. After the raid on the King’s Inns on June 1, 1920, when the IRA seized weapons, Kevin took a Lewis machine gun over to his place in Fleet Street and then “adjourned to our usual spot in Matassa’s, Marlboro Street for coffee, etc”.

Even with the curfew imposed in February 1920, Dublin still spilled over with life. “Meet at the Grafton Picture House,” read an advertisement on the street. Kevin frequently met friends there.

In a letter to his friend Bapty Maher (who later married Kevin’s sister Shel), he wrote from the family home in Carlow:

I wrote you a letter about a month ago and I don’t know if you ever got it as I’m not sure if I put the right address on it. Anyway how are you since I saw you last? You might write to a fellow you know, now and then, and say how things are. Now answer this soon and answer it to ‘my town house’ as I’m nearly fed up here … yours to a cinder, Kev.

Three weeks later, he still had no answer from Bapty, by which time he was back up in Dublin at 8 Fleet Street.

How the devil are you at all? You know you might write to a fellow once in a while. I wouldn’t mind me not writing because I’m very busy, pictures, National Library (ahem) and Grafton (5–6pm), but a fellow like you – a bloody gentleman of leisure, you know it’s unforgivable.

By the way that bloody bastard never came with the suit with the result that I have to borrow one for a dance tomorrow night. Write and tell him that I say he’s a ——so and so etc.

When will you be up in town? You ought to come for a céilídhe (College of Science) on the 30th Jan … Yours till hell freezes, Kevin.”

When you are the descendant of a hero, you live in their shadow. I tried to run from the overwhelming charisma of this boy-hero-great-uncle, whose story was sung by Paul Robeson, Leonard Cohen and every traditional Irish band you can think of.

Yet my grandmother Monty, Kevin Barry’s sister, would not allow the song to be sung in the house. It was maudlin, she said.

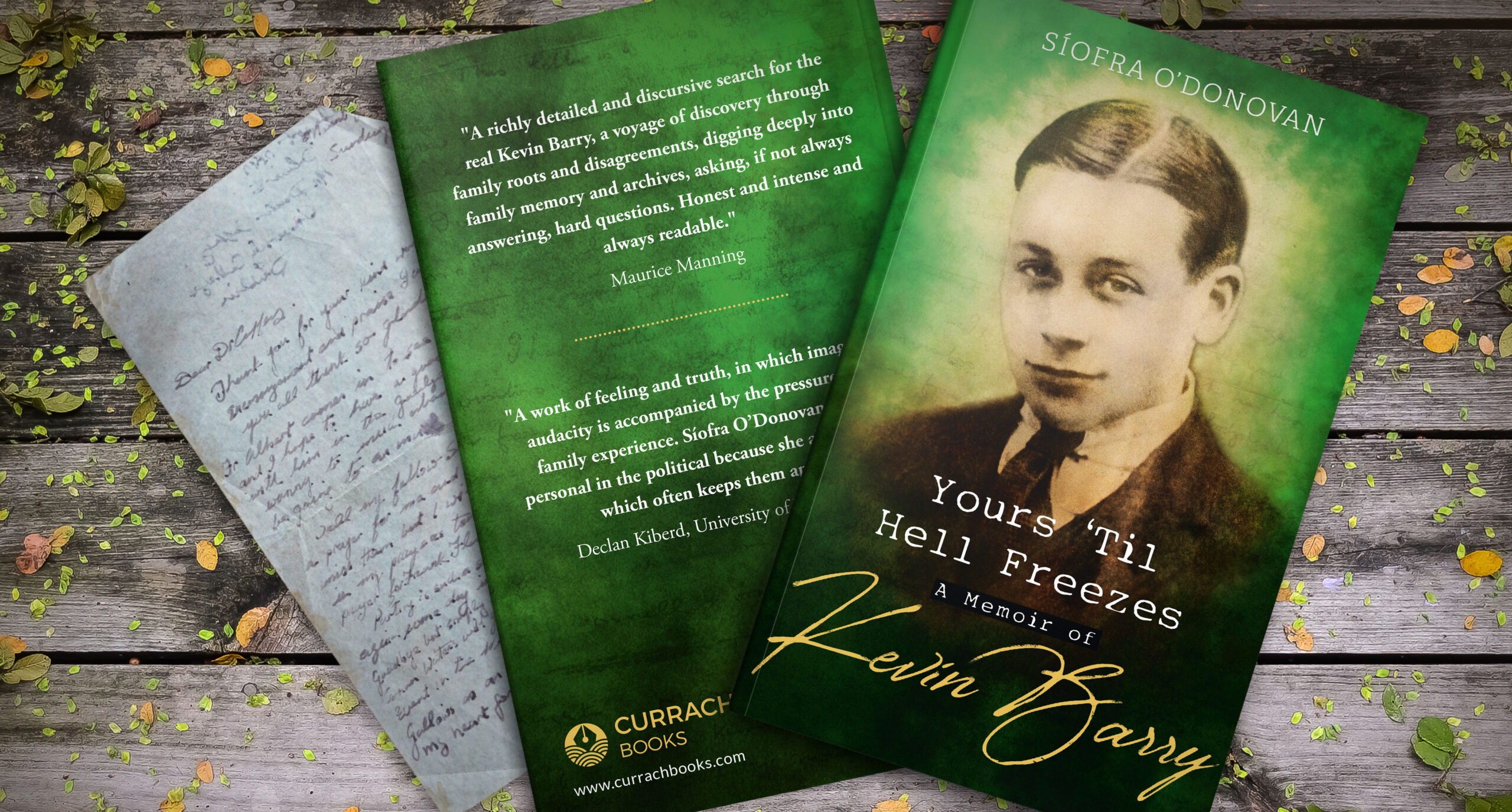

But Kevin wasn’t maudlin. An oval portrait of him hung in my father’s study — a copy of a painting by somebody in the H Company of the IRA. Kevin’s face and shoulders had a slightly airbrushed look, set against a monochrome and patriotic green background.

Rare photo of Kevin Barry.

Kevin had a quiff of hair like Tintin and was wearing a trench coat with the collar upturned. He beamed eagerly around my father’s study, like a friendly family ghost.

Beside this portrait was another one of my grandfather, Jim O’Donovan, in a rectangular frame. A true die-hard, my grandfather’s convictions had him locked up long after the War of Independence. His face, in the portrait and in real life, was sterner and more chiselled.

My grandmother Monty was a woman of acerbic wit and sharp intelligence.

After my grandparents died, my father wanted me to carry the chattels of our family history, but initially I did not want to do it.

He would sit in his green armchair and tell me stories of how Kevin Barry cycled over the Wicklow hills to drink in the hotels in Glendalough and Aughrim, how my grandfather locked himself in a room at night in the family home in Shankill, Co Dublin, speaking German to his secret friends in Nazi Germany.

How my great-aunt Kitby, Kevin’s older sister, sailed to America with Countess Markiewicz, on De Valera’s orders, to fund-raise for the Republic. But my father always came back to Kevin.

Kevin spinning around on his bike in his Belvedere cap, drinking, dancing, pulling Belgian girls, out on the streets in ambushes, down alleyways carrying arms. And in the end, hanging on the gallows, just like in the song.

The stories seeped into me. I resisted, but there was nothing I could do, because they were part of me. When my father was 12 years old the Nazi spy, Hermann Görtz, was put up in my father’s room in the family home. Görtz moved on to the garage or the orchard by day, hiding behind the eucalyptus tree.

As far as my father was concerned, he was a hero, dropped from a Heinkel 111 bomber near Ballivor, Co Meath, where an amused farmer asked, “Do you not know Ballivor?”, when the spy inquired as to where on earth he was.

Although I grew up with these gripping tales of espionage and family militarism, it was ultimately Kevin Barry who made the greatest impact. I took refuge in our family hero, the boy who beamed at me from the oval portrait in my father’s study.

I wrote essays about Kevin for history class, described the ambush on the Monk’s Bakery in detail. I could see his face as he was driven with the British soldiers to Bridewell prison.

Irate, but amused. I wrote about the arrest on September 20, 1920 and about the short time he spent in Mountjoy prison before his execution on November 1.

He was hanged the day before my birthday and, although we lived decades apart, his death was a shadow that followed me everywhere.

‘Yours ’Til Hell Freezes — A Memoir of Kevin Barry’, by Síofra O’Donovan,is published by Currach Books. Available here