Garda Review – October 2021

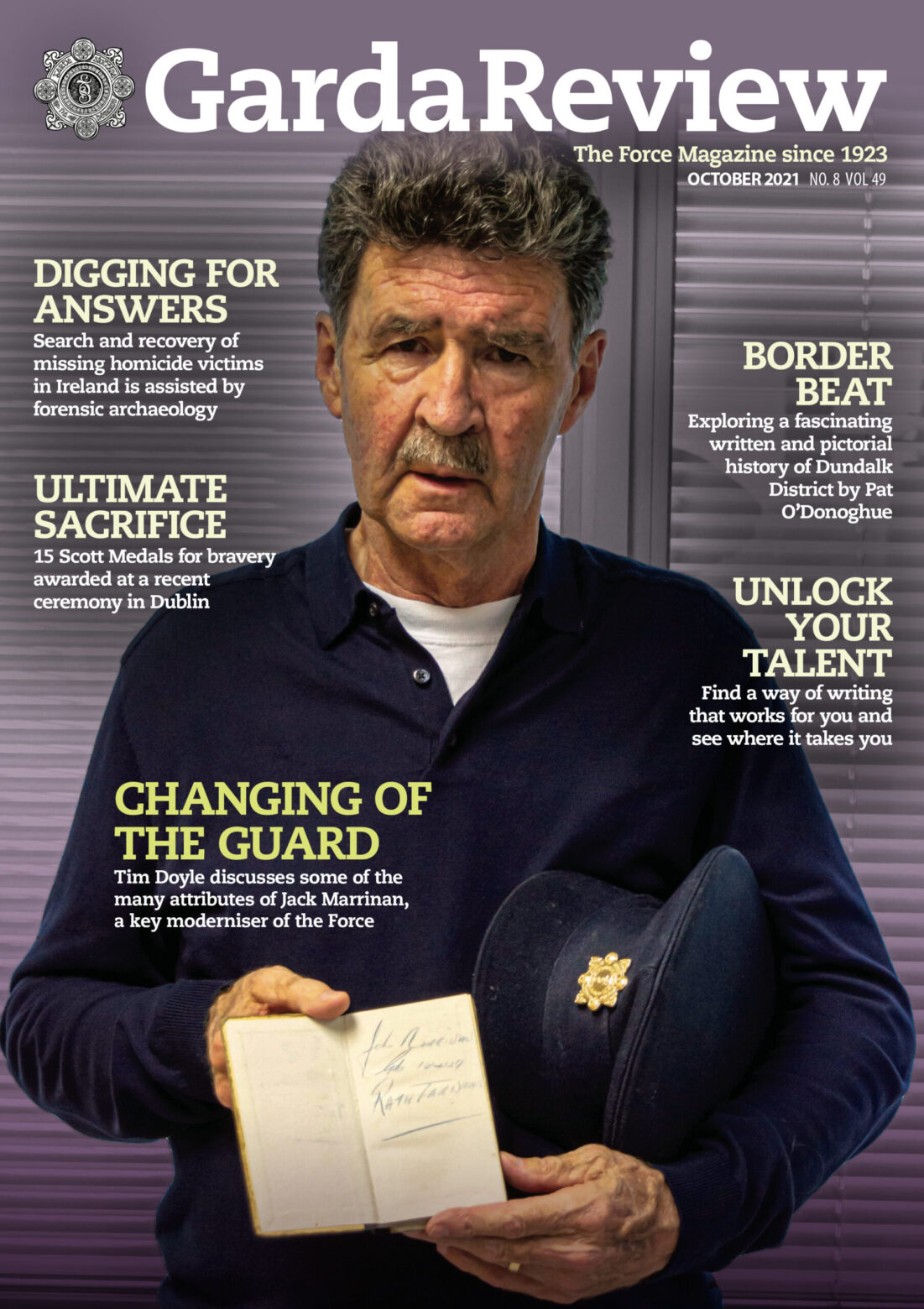

A KEY MODERNISER

Tim Doyle discusses some of the many attributes of Jack Marrinan, a transformational figure in the Force at a time of great social and economic change.

My recently published book Changing of the Guard- Jack Marrinan’s battle to modernise An Garda Síochána, draws on the testimony of Marrinan, and his family, as well as a wide circle of members who served with him during the second generation of gardaí – the 1950s to 1980s.

As a 1953 joiner, Marrinan’s background, training and early service are well covered, but it was the evening of November 4 1961 when the ferment of discontent that smouldered and flickered throughout that decade burst into flame in Dublin’s Macushla Ballroom.

As a 1953 joiner, Marrinan’s background, training and early service are well covered, but it was the evening of November 4 1961 when the ferment of discontent that smouldered and flickered throughout that decade burst into flame in Dublin’s Macushla Ballroom.

Following an earlier pay award in which gardaí with under five years’ service were ignored, almost 1,000 members attended the unauthorised meeting. It was mayhem until Marrinan took charge. Within days, along with 10 others, he was sacked, but to the consternation of garda authorities, as well as Taoiseach Sean Lemass, and Justice Minister Charles J Haughey, he led the insurgents on a countrywide campaign, and it took the intervention of Archbishop John Charles McQuaid to bring them back into the fold.

Within a week all the gardaí were reinstated. Three months later Marrinan refused promotion to the rank of sergeant and shortly after he was unanimously elected General Secretary of the newly inaugurated Garda Representative Body – GRB. He sought, as his assistant his close friend Michael Conway who had already organised the Garda Group Assurance Scheme which was of critical importance to widows and orphans. He also encouraged members to join the Garda Benevolent Society, and during the 1950s ran the Garda Medical Aid Society on his own. Conway became Boswell to Marrinan’s Doctor Johnston, and both remained together throughout their careers.

Marrinan took over the Force magazine, Garda Review and wrote hard hitting editorials which within a short time impacted on the national press and media. He also introduced a broadsheet information circular, as well as a bi-annual GRB Newsletter which guaranteed that all members were updated on emerging developments. He also retained the expertise of economist Garret FitzGerald and Legal Advisor Michael O Kennedy and the exceptionally talented writer Conor Brady.

In 1963 the GRB successfully negotiated their first independent pay award, when Marrinan took on the redoubtable Secretary of the Department of Justice, Peter Berry on paper and won. A second claim was conceded in 1966. These increases resulted in a weekly increase of £3 for recruit gardaí and pro-rata increases on all the incremental scales. In addition, gardaí over 21 years were awarded an extra £1 per week and those under that age and ban gardaí were awarded 15 shillings.

On September 25 1968 the GRB seized the initiative and forced Justice Minister Michael O Morain to set up the Conroy Commission. Its terms of reference were ‘To examine, report and make recommendations on the remuneration and conditions of service of An Garda Síochána’.

The 250-page Conroy Commission Report was published at the end of January 1970 and made 52 recommendations on virtually every aspect of garda service; accommodation, allowances, development of managerial and leadership skills, discipline, education, hours of duty (including new rosters and night duty pay payments), pensions, recruitment, representation, training, uniforms, welfare, and widows. It also introduced two new and exciting terms to the garda vocabulary- rest days and overtime, as well as outlining relevant payment conditions.

Two months later Conroy was completely overshadowed with the savage murder of one of our most revered and fearless colleagues Garda Dick Fallon.

This hampered Conroy’s roll out, and along with the Troubles on the doorstep, Marrinan’s Garda Review editorial prophetically foretold – “The murder of Dick Fallon introduced fears in every garda spouse and family that when a loved one went on duty there was now a worry about him or her ever coming home”.

Jack Marrinan

In the mid-1970s Marrinan was critical of his authorities. He wrote, “The relationship between the Justice Department and our Commissioner deprives the latter of a good deal of personal responsibility and initiative that one would expect from a man of his eminence. I worry about our authorities rushing to employ extra gardaí and packing them off to the Border armed with 18 weeks training without any clear long-term plan. These members do not have the structured apprenticeship of being allocated in small numbers to stations up and down the country, arriving at intervals of two or three years that gave the previous cohorts time to settle in. Too many members spending time on posts and roadblocks have no chance of on-the-job satisfaction or getting inside their profession.”

Between May 1974 and October 1976 booby trap bombs came south with a vengeance. In the capital city we lost 33 innocent people with 10 times as many injured. Crime was spiralling; up 30% in five years. In March 1976 the Dublin to Cork mail train was held up at Sallins and following a garda investigation five individuals were charged. The Irish Times published a series of articles claiming that brutal interrogation methods were employed by gardaí and coined the phrase ‘the Heavy Gang’.

At the time I was a crime detective in Store Street. Bomb scares and armed robberies were everyday events. Allegations of garda misbehaviour were prevalent. During one investigation, allegations of assault were made against me, and I was charged with a number of serious criminal offences. If convicted I would certainly be discharged from the Force and could be imprisoned.

John Robinson was my superintendent and one day he jammed a large envelope inside my topcoat. It was a copy of the Garda Review and he had marked a section where the GRB had decided to provide legal aid for members who were subject to criminal investigation for duty-related matters.

Jack Marrinan talked to me, not at me, and provided top class legal advice; Hugh O Flaherty Senior Council and John Gallagher, a former garda turned barrister. The trial lasted two days, followed by a two-week reserved judgement.

Later, following a not guilty verdict, my gratitude to Jack Marrinan gave way to a fascination with the man, whose measured response saved my career and led to the research and writing of this memoir.

In the mid`1970s Justice Minister Cooney announced that he had commissioned management consultants Stokes Kennedy and Crowley (SKC) to examine the administration and structures of An Garda Síochána.

Immediately, Marrinan responded, “that determining the role of An Garda Síochána is not a job for management consultants, no matter how eminent. As our society becomes more developed and complex, our role must change. It is no longer merely keeping the peace; our workload has increased enormously. In the past five years this Force had lost three valiant members, while at the same time the emphasis has been placed on the rehabilitation rather than the punishment of crime offenders. It’s like choosing the wallpaper for a house long before it is built.”

Following a two-hour meeting with SKC, Marrinan reiterated that the long-term discontent unearthed by Conroy had not been resolved. He quoted the judge’s conclusions in Paragraph 1266, but the GRB came away fully convinced that the SKC process had been captured by the authorities and it would do their bidding.

The Stokes Kennedy and Crowley report was never published.

At the time Marrinan remarked that it was obvious that only the GRB had remained constant in their demands for the full implementation of Conroy. Independence from government had been inherited from the last paragraph of the Conroy Report and Marrinan’s push for its implementation had been constant.

In mid-1976 Justice Minister Patrick Cooney chose the presentation of Scott Medals in Templemore to warn gardaí against panicking the public and defined loyalty as the willingness of the Force to stay silent even when suffering from legitimate grievances.

This brought a blazing response from Marrinan’s editorial and resulted in the Commissioner dispatching a high-ranking deputation to Eamon Barnes, the newly appointed Director of Public Prosecutions, to charge Marrinan, along with other members of the Review editorial board with usurping the functions of government.

Mr Barrins declined to do so.

When Gerry Collins became Justice Minister in 1977, he found on his desk the completed GRB submission on reforming the body and reconstituting it as the Garda Representative Association. The GRA would be organised nationwide with 110 districts and 26 divisions, each of which would have an elected chairman, secretary, a minimum of three members per division and a delegate to the yearly annual general conference. Members would serve a three-year period.

The early 1980s was a torrid time. In February 1980 Marrinan was unwell and needed a triple heart bypass to keep up his work rate. Moving on, his workload trebled, and he would serve under seven Justice Ministers and four Commissioners.

Over the first five years of the 1980s we would lose a total of eight garda colleagues. This was the most tragic era in living memory. Marrinan and his GRA colleagues lambasted successive governments to introduce and fast-track new investigative powers for serious crime. The problem was political; with four different Justice Ministers between 1977 and 1982. In fairness Commissioner Paddy McLaughlin backed the GRA’s demands.

Eventually, in August 1984, new powers were approved, but the official side withheld sections of the Act until the gardaí agreed in totality with the Garda Complaints Act.This included two astonishing sections which Marrinan and his successor John Ferry fought tenaciously until they were amended. The Garda Complaints Act was published on June 13 1986. However, in the meantime too many members of An Garda Síochána had suffered grievously.

In 1983 newly appointed Justice Minister Michael Noonan, having accepted the need for a police authority, opened a special GRA Conference on policing reforms in Dublin. The keynote speaker was Mary McAleese, and in a challenging, uncomfortable speech to those in authority she pulled no punches and articulated many of the problems the GRA had been highlighting for years.

Immediately its impact was overtaken by events. Sergeant Patrick McLoughlin was based in Dunboyne and his family home formed part of the garda station. One night while asleep he was wakened and answered his upstairs window. He was immediately shot dead. He was 42 years of age and married with three children.

Also, at the time subversive threats were made against Marrinan and his family, including his school-going children.

Marrinan claimed that during his time the protection of property overruled the protection of his members. In 1984 following Detective Frank Hand’s savage murder, he wrote, “that subversives had identified the quickest, safest and most efficient way of getting their hands on the money was to eliminate the garda escort. Life did not matter. Gardaí were expendable.”

In 1985, following years of intercession by the GRA, Commissioner Wren set up an advisory committee to make recommendations on training from recruiting intake stage. He also stated the committee would consult fully with Garda Representative Associations. Marrinan welcomed the choice of chairman; Dr Tom Walsh, an independent and respected public figure. The sole garda representative in the 10 strong committee was Deputy Commissioner Eamonn Doherty. Marrinan reckoned he was back in the never-never land of the STK report, which was so secret that nobody of garda rank ever got sight of it.

However, much of what the GRA had already recommended was contained in the Walsh Report. The basic training was to be replaced by a two-year programme. Policemen and women working in partnership with other agencies in helping to maintain law and order. No longer a police force; more of a police service.

This was music to Jack Marrinan’s ears.

In July 1989 Jack Marrinan retired from An Garda Síochána. Nearly all of the advantages that gardaí enjoy today in their service are built on the foundations he established. He passed away on July 12 2012. GR

Tim Doyle is a retired garda. Changing of the Guard- Jack Marrinan’s battle to modernise An Garda Síochána is published by Currach Books and is available in all good bookshops.

All royalties from this book will go to the Irish Kidney Association.