An exclusive excerpt from Wild Stories from the Irish Uplands by John G. O’Dwyer

Nobody else has influenced Irish lives so profoundly. Celebrated in more countries than any other, his feast day has morphed into an international event that involves the greening of hundreds of the world’s most iconic locations. Andrew, George and David, the saintly men of Ireland’s nearest neighbours, hardly get a look in by comparison, while this country’s national apostle has gone mega, becoming the world’s most commercially exploited saint.

Nobody else has influenced Irish lives so profoundly. Celebrated in more countries than any other, his feast day has morphed into an international event that involves the greening of hundreds of the world’s most iconic locations. Andrew, George and David, the saintly men of Ireland’s nearest neighbours, hardly get a look in by comparison, while this country’s national apostle has gone mega, becoming the world’s most commercially exploited saint.

St Patrick’s Day has morphed into a global behemoth, an international goodwill fest for Ireland, of almost inestimable PR value. It is at this time our diaspora extravagantly strut their stuff, reminding others not fortunate enough to have ancestors from the Emerald Isle of their own luck at being Irish. Yet, we understand little about the individual behind the extravaganza as the cult of sainthood has, as is often the case, hugely obscured the person.

From his own words written in Latin, we know Patrick was the son of a wealthy Christian living in Britain. Aged 16, he was captured by Irish raiders as the terminally weakened Roman Empire was no longer able to defend its borders. If his personal account is true – there is no collaborating evidence – he was then sold to slavery in Ireland. During this period, he became increasingly religious and turned to long periods of prayer. After six years, he experienced a religious epiphany while tending flocks and believed God was calling him home. Motivated to escape he fled for 200 miles, which in pre-historic Ireland would have been, for a penniless, escaping slave, considerable accomplishment in itself, that would probably require some divine intervention. He then found a ship that conveyed him away from Ireland. After many difficulties, including becoming lost in a wilderness, he eventually returned to his family. Later, he studied Christianity and following an apparition, which suggested the Irish people were calling him back, he returned to Ireland as a bishop and was instrumental in converting the island to the new faith.

It is, of course, almost inconceivable that Patrick came to an island that had not previously been exposed to the Christian faith. The Roman Empire had, after all, been Christianised by the Emperor Constantine more than a century before his arrival and Ireland had particularly strong trade links with Britain. Simple narratives are, of course, the most powerful, so the early Irish Church cannily promoted the first bishop of the dominant See of Armagh in a series of hagiologies. St Patrick, who has never been formally canonised as a saint, was entirely credited with converting the people of Ireland to Christianity. This served the purpose of making Armagh the most important Irish bishopric, while other contemporary saints and important Christian missionaries such as Declan and Ailbe were condemned to relative obscurity.

Outside of these predisposed writings, facts are scant about this British born saint who has come to be regarded as quintessentially Irish. Mythology compensates, however, with a wonderfully

Outside of these predisposed writings, facts are scant about this British born saint who has come to be regarded as quintessentially Irish. Mythology compensates, however, with a wonderfully

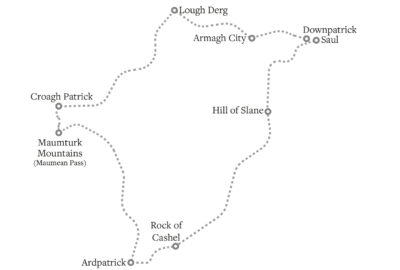

colourful Patrician narrative. Often depicted as carrying a cross in one hand and a shamrock in the other, Patrick came to Ireland at a time when the Irish language did not possess a written alphabet and so an expansive oral mythology evolved around Ireland’s national apostle. This was initially passed on in the spoken word from generation to generation as a series of richly embroidered stories. It is sometimes said these myths from the past are always true, for they accurately reflect human aspiration at a particular point in history. So, let us now set out on our magical and mythical journey in the highly mythologised footsteps of Ireland’s patron saint.

***

The idea of self-sacrifice is central to pilgrimage and we now move back to a time before the necessity of a walking journey was engineered out of our lives. We must lace up the hiking boots securely for things are about to get tougher on Ireland’s holiest mountain. Bearing many resonances from its origins as a place of pagan worship, Croagh Patrick is a mountain that must surely have been surprised by its own extraordinary popularity. It is climbed about one hundred thousand times annually for it is reputedly the mountaintop on which St Patrick fasted for 40 days. Despite this hardship, he apparently remained in a mood to be helpful towards the people of Ireland for he took the time out from prayer and privation to banish all species of snake from the island. These days this might be considered a sinister assault on biodiversity and Patrick would probably have found himself extensively trolled on social media. But these were different times, it was the snakes that were considered sinister and Patrick’s popularity rose steeply.

On the uncooperatively steep ascent you will probably conclude Patrick was indeed a tough cookie, with all the credentials to qualify him as Ireland’s first mountain climber. The path is undoubtedly demanding, and will probably seem relentless as you plough upwards through rivers of scree. About half way up, the slope eases for a while at a point where it intersects with the Tochar Phádraig: the 35km pilgrim path from Ballintubber Abbey which is described in Chapter 10. The toughest bit has still to come and as we tackle it, I am going to take your mind off the ascent by setting you a little challenge. Walking the pilgrim paths of Ireland while writing my previous book, a question occurred to me about what motivates people to go on pilgrimage. I mulled over this through many a long walk and finally the word “DARE” came into my head as an acronym for pilgrim motivation. Is it all about discovery, mainly personal self-discovery; appreciation, for a favour bestowed; remembering, a special person; or finally escape, when the pressures of life seem overwhelming? If you think the answer to this question is yes, you can now contemplate

which of the above motivates you. If you think the answer is no, you can shorten the ascent by trying to figure out your own more accurate acronym.

After some huffing and puffing, the seemingly interminable upwards path will eventually meander to a conclusion. Immediately obvious on reaching the summit is the relatively modern and not

noticeably attractive 20th Century chapel that is rather incongruously set on its rocky throne. Fear not, however, your efforts have not been wasted for the charm of this mountain lies not in the immediate but in the distant. On a clear day, we will view a landscape little altered since St Patrick reputedly trod these self-same stones. Majestic vistas open from the great sweep of multi-islanded Clew Bay to the pristine wildness of the Mayo Mountains and moorlands beyond.

Obviously, Patrick isn’t feeling the best after his fast, so you will probably not be surprised that he refrains from climbing on his next visit, which is to Lough Derg, Co. Donegal.

Wild Stories from the Irish Uplands by John G. O’Dwyer is available here.